On this page:

Message from the Minister

Welcome to the twentieth edition of the Victorian Water Accounts.

The longevity of this record through two decades of dry, wet and in-between water resource conditions provides a wealth of water information for researchers, policy makers and water users in general.

For the second year, the report is available on this new Victorian Water Accounts website. The site features several improvements with new interactive rainfall decile maps and more options to download current and historical data going back to 2003-04. The recent enhancements are part of a 20-year journey for this important reporting resource.

The 2022-23 Victorian Water Accounts tell the story of a wet year with above average inflows. It is one of only five years out of the 20 in this series in which total river flow volume across Victoria was higher than the long-term average.

Major flooding during spring 2022 negatively affected communities across many of our river basins. This is likely to have been influenced by a rare third consecutive La Niña event that we experienced during spring and summer.

Almost all of Victoria received above average or very much above average rainfall for the year. The total inflow volume was 217% of the long-term average, the highest in the 20 years of reporting.

Consistent with the previous year which was also wet, Victorian water users continued to benefit from low levels of restrictions on water use and good allocations to regulated system entitlements. Total water storage levels rose during the year from 84%-92% full.

The total volume of water available – including surface water, groundwater, recycled water and desalinated water – was over 50,000 gigalitres (GL), larger than the almost 35,000 GL available the previous year. For a comparison, a single GL is the equivalent of around 400 Olympic Swimming Pools.

I would like to finish by making the point that while the 2022-23 and 2021-22 years have been wetter than average, we know that these occurred against background trends of a warming, drying climate and a growing population. The 20-year scope of these reports also includes the very dry final years of the Millenium Drought. We must keep that period in mind when considering what a climate change-impacted future may look like and its impact on our precious water resources. Enjoy browsing this edition of the Victorian Water Accounts.

Enjoy browsing this edition of the Victorian Water Accounts.

THE HON HARRIET SHING

Minister for Water

October 2024

Overview

Wetter conditions

More rainfall was received across the state, with more water flowing down rivers and into storages than the previous year.

More water was available

The total available volume of surface water, groundwater and recycled water was higher than the previous year. There was less desalinated water produced.

Fewer stream restrictions

There were fewer restrictions on licensed diversions from unregulated streams and groundwater than the previous year.

Urban restrictions were the same

All towns remained on permanent water-saving rules for the whole of 2022-23, the same as the previous year.

Water availability

- Most of the state received more rainfall than in the previous year. Rainfall was average in South and East Gippsland and very much above average in most of the rest of the state.

- There was a negative Indian Ocean Dipole from August to November 2022 and a La Niña event from September 2022 to March 2023. Both events contributed to increased rainfall across the state.

- More water was available than the previous year (50,635,661 ML in 2022-23 compared to 34,680,425 ML in the previous year).

Rainfall

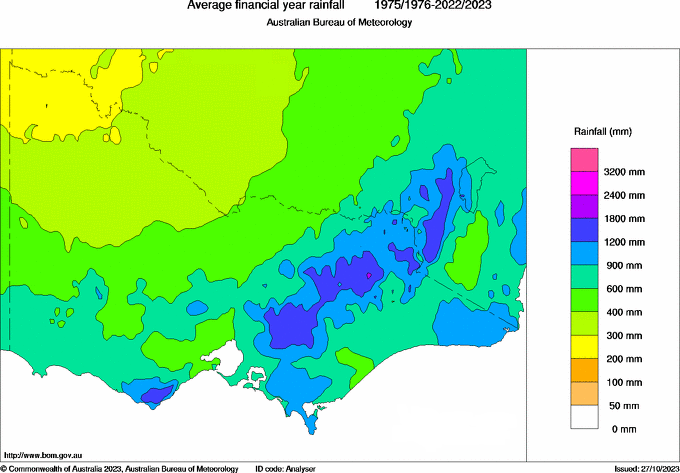

Long-term average rainfall in Victoria (July 1975 to June 2023 - Figure 2a) varies from less than 300 mm a year in the north-west of the state to up to 1,800 mm a year in the alpine area of the north-east.

Through Spring 2022, a series of low-pressure systems or surface troughs travelled over south-east Australia, bringing heavy rainfall and storms. The cumulative impact of these events on catchments and waterways led to major flooding in the Murray, Ovens, Broken, Goulburn, Campaspe, Loddon, Avoca, Wimmera, Snowy, Maribyrnong and Werribee basins.

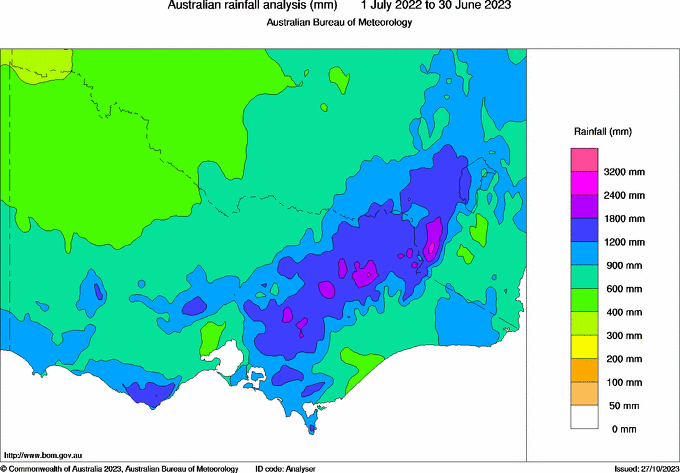

The range for total annual rainfall received in 2022-23 varied across the state from 300 mm to 3,200 mm (Figure 2b). Most of the state received more rainfall than the previous year.

- The lowest rainfall - between 300 mm and 600 mm - was received in the north-west, in parts of coastal West Gippsland and the western Port Phillip Bay region.

- The highest rainfall - receiving over 1,800 mm - was received in parts of the Yarra Ranges, the alpine region, central Hume and the far north-eastern corner.

When compared to the 1975 to 2023 reference period, the rainfall received in 2022-23 was close to average in South and East Gippsland and very much above average in most of the rest of the state (Figure 3). The highest recorded rainfall in the reference period (1975 to 2023) was received near Goroke in the Wimmera, around Mount Buller and over parts of the upper Murray catchment.

Figure 3: Rainfall deciles 2022-23

Sourced from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology

The various layers on Figure 4 show the seasonal pattern of rainfall during the year, relative to the 1975-2023 reference period.

- Winter rainfall was close to average across most of Victoria.

- Spring rainfall was the highest recorded in the reference period across most of northern and western Victoria.

- Summer rainfall was below average across much of central, north and west Victoria.

- Autumn rainfall was above average across much of central and southern Victoria, and close to average elsewhere.

Figure 4: Seasonal rainfall deciles 2022-23

Sourced from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology

La Niña and a negative Indian Ocean Dipole

On 2 August 2022, the Bureau of Meteorology declared that a negative Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) had been established, bringing with it above average winter-spring rainfall. On 13 September, the Bureau of Meteorology announced that La Niña had established itself in the tropical Pacific, further increasing the chances of above average rainfall in Victoria. The IOD began to weaken in November 2022 and returned to neutral in December 2022.

La Niña continued until mid-March 2023 when most of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation indicators began to ease.

Total water available

Overall, the total available volume of Victoria’s surface water, groundwater, desalinated water and recycled water in 2022-23 was 50,635,661 ML (Figure 5 and Table 2), more than the amount available in the previous year (34,680,425 ML).

- More surface water and recycled water was available.

- Slightly less groundwater was available, largely because the Glenelg water supply protection area was abolished since the previous year, and its permissible consumptive volume was revoked.

- Less desalinated water was produced.

Table 2: Total available water

Response to water availability

The amount of water available for consumptive and environmental uses varies from year to year. The entitlement and planning frameworks include mechanisms to conserve and share water between users in response to seasonal variability and water shortages. We have provided more information on these mechanisms in the How is water managed?

In 2022-23:

- there were higher seasonal allocations (Statewide surface water)

- there were fewer restrictions on licensed diversions from unregulated streams (Statewide surface water) and groundwater (Statewide groundwater)

- all towns remained on permanent water-saving rules, with no additional restrictions on use (Statewide water supply)

- no water carting was required to supplement water supplies

- there were no temporary qualifications of rights to water.

Water use

Water for all types of uses in Victoria is taken from reservoirs, streams and aquifers under entitlements issued and authorised under the Water Act 1989.

Read more about different uses under the entitlement framework in How is water managed?

In 2022-23, 3,755,966 ML of water was used (for consumptive and environmental purposes), less than the previous year (4,421,547 ML) (Figures 6 and 7 and Table 3). This includes surface water, groundwater, recycled water and desalinated water.

- The amount of water used for consumptive purposes was 3,143,687 ML (less than the 3,413,123 ML used in 2021-22).

- The amount of water delivered to the environment was 612,279 ML (less than the 1,008,424 ML delivered in 2021-22).

Table 3: Water use by type

Water entitlements

The total volume of entitlements changes each year as new entitlements are issued or existing entitlements are modified. All river basins in the state have a cap on entitlements, and groundwater management units have a permissible consumptive volume (PCV), which limits the volume of water that can be allocated. In areas that have reached the cap/PCV and allocated all available water within the limit, no new entitlements are created unless water-savings are made, so there is no net increase in entitlement volume.

Read more about entitlements in How is water managed?

In 2022-23, entitlement volumes were slightly higher than the previous year due to some changes to surface water entitlement volumes (Figure 8 and Table 4). This was mainly due to the Goulburn-Murray Water Connections Project delivering water-savings to irrigators, retailers, and the environment. Visit Statewide surface water for more information.

Traditional Owner organisations hold surface water and groundwater entitlements. The entitlement volume held by these organisations is included in Table 4 in the consumptive entitlement volume totals. On 30 June 2023, this volume was around 6.9 GL. The organisations used for this estimation include Registered Aboriginal Parties as well as other known Aboriginal organisations and cooperatives.

Table 4: Water entitlements by type

Evapotranspiration

Evapotranspiration is the sum of all processes by which water moves from the land surface to the atmosphere via evaporation and transpiration. Evapotranspiration amounts vary considerably across Victoria depending on a range of factors including rainfall conditions and land cover.

- Averaged across Victoria as a whole, evapotranspiration in 2022-23 was estimated to be 686 mm.

- This was about 22% above the long-term average (the post-1975 historic climate reference period) evapotranspiration, and 11% more than 2021-22.

- When estimated at a basin scale, evapotranspiration was generally high. All Victorian basins experienced annual evapotranspiration above the long-term average conditions. This was due to above average rainfall in 2022-23.

- In general, 2022-23 was a wet year, with rainfall exceeding the long-term average conditions in all river basins. Averaged across Victoria, the annual rainfall was 34% more than the long-term average, and 17% more than 2021-22.

- Catchments in the north of the state received the most rain relative to the long-term average, with the Mallee basin receiving 61% more rain, followed by the Loddon and Avoca basins with 56%.

- The driest river basins were found in the south-east, with East Gippsland experiencing only 3% more rain than the long-term average. This contrasted with some basins in the south-east receiving more than 40% of the long-term average in 2021-22.

- Read the for more detail on evapotranspiration in 2022-23.

Looking for more information?

The VWA reports on availability and use across surface water, groundwater, water supply and water for the environment. The structure has changed a bit from the Accounts prior to 2021-22. If you would like to find information equivalent to specific sections in our historical PDF report structure - go to our mapping

Statewide summaries

Learn about different aspects of water availability and use across Victoria in 2022-23.

Local reports

Explore the local water reports by surface water, groundwater or water supply.