On this page:

About surface water

Surface water is water that occurs or flows on land. It includes water in waterways and in lakes, reservoirs, dams, wetlands and other water bodies. A waterway is a river, creek, stream, watercourse or natural channel where water regularly flows. This flow does not need to be continuous.

River basins are the primary reporting unit for surface water information for these Accounts. Water resources explains more about surface water resources.

This summary reports on statewide surface water availability, use, compliance and trade for 2023-24.

A breakdown of availability, use and compliance in each of the 29 river basins is provided in the surface water local reports.

2023-24 overview

Less water was available

The volume of surface water available in river basins was more than 50% lower than last year.

More restrictions on licensed diversions

There were more restrictions on unregulated stream sections than in the previous year.

About the same seasonal allocations

Water availability from seasonal determinations remained high, with significant low-reliability allocations.

More water was used

Around 13% more water was taken for consumptive use and environmental deliveries than the previous year.

When compared to the previous year, in 2023-24:

- less water (total streamflow) was available (21,088,949 ML compared to 49,028,935 ML in 2022-23 when Victoria experienced significant flooding)

- there was less water in storages (levels in Victoria’s major storages were 82% in June 2024 compared to 92% in June 2023)

- a similarly high allocation was made to water share holders

- there were more restrictions on licensed diversions from unregulated streams (a peak of 80 stream sections restricted in March 2024 compared to 52 in March 2023)

- no desalinated water was produced (0 GL compared to 4.1 GL in 2022-23)

- a similar volume of surface water was diverted for consumptive uses (2,986,799 ML compared to 2,850,249 ML in 2022-23)

- more water was delivered for environmental purposes (933,031 ML compared to 612,279 ML in 2022-23)

- there was a higher volume of trade of allocation, less trade of water shares, and a reversal of net interstate trade (from net import to net export).

Table 1 reports on the total available water, total entitlements and total use (consumptive and environmental). In 2023-24, 3,919,830 ML of surface water was taken for consumptive and environmental purposes in Victoria (Table 1).

Table 1: Available surface water and use

Water availability

Surface water availability across the state is presented as a report on streamflows and storage levels. Streamflow is equivalent to catchment inflow in the river basin water balances in each of the surface water local reports, and the terms are used interchangeably throughout the Accounts

Overall, there was less water available in 2023-24 than the previous year:

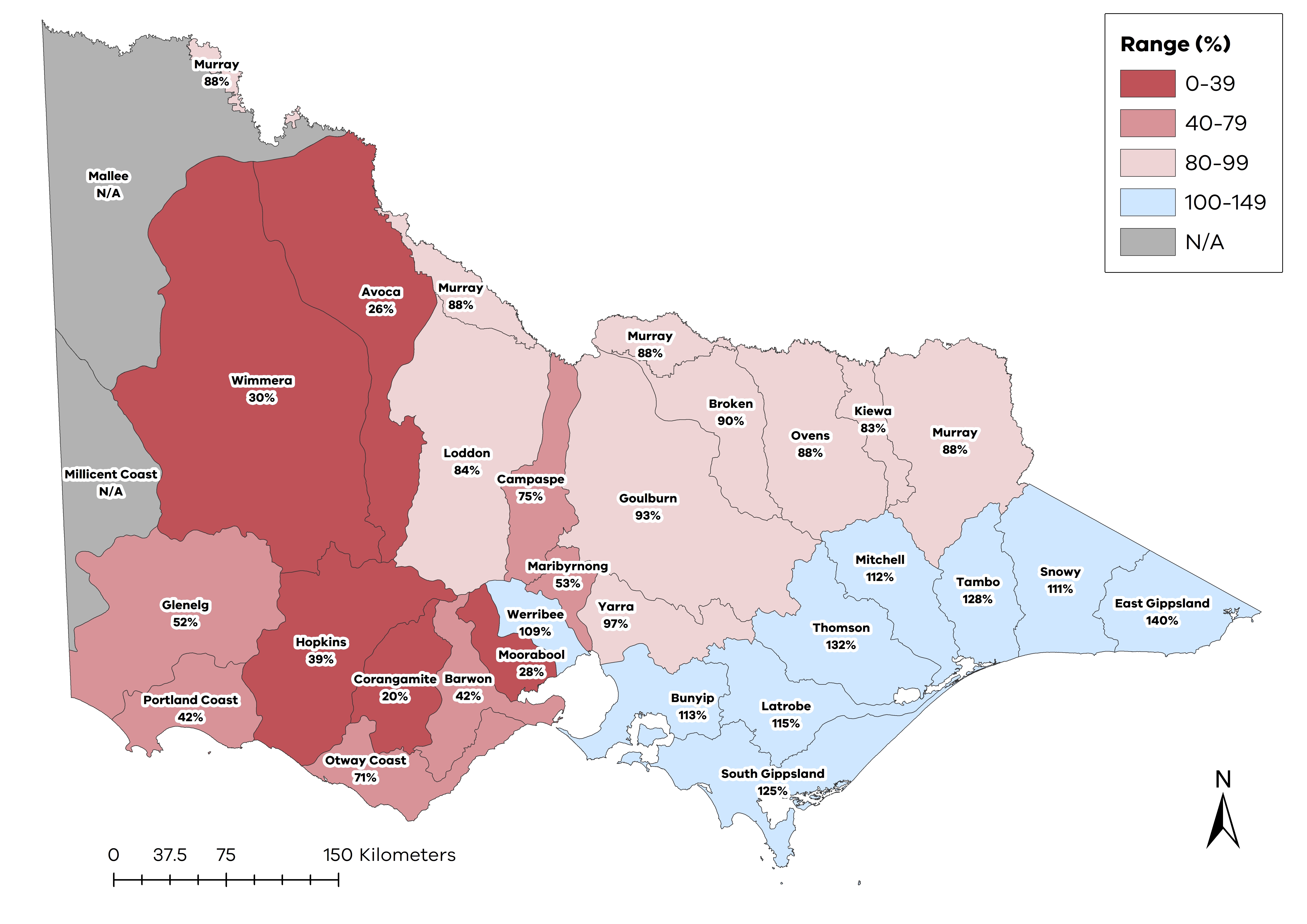

- 93% of long-term average streamflows were received in Victoria (compared to 215% in 2022-23 when Victoria experienced significant flooding).

- Total Victorian storage levels reached a peak of 95% in October 2023 compared to the peak of 98.4% in December 2022.

For more information on rainfall and water availability, see Year In Water.

Total Victorian streamflows

Review of long-term surface water availability

For the 2023-24 Accounts, the estimates of long-term water availability, also known as long-term average inflows, were updated for the first time since the 2018-19 Accounts. The update has used an additional 5 years of data to better represent the current climate (1975 to 2024). Changes were made to all long-term average inflow estimates except for the Mallee, Millicent Coast, Bunyip and Snowy basins. The updated long-term average inflow has been applied to this year and the previous year’s volume on this page.

More detail on the update can be found in the method tab of Figure 1 and in Water Explained.

In 2023-24, the total annual streamflow volume for Victoria was 21,088,949 ML, 93% of the long-term average inflows received from 1975 to 2024 (22,767,600 ML). This was less than the volume in 2022-23, which was 49,028,935 ML, 215% of the long-term average, when there was significant flooding in Victoria.

In 2023-24:

- all river basins had lower annual streamflow volumes than the previous year

- there was considerable variability in the total streamflow (relative to the long-term average) per basin (Figure 2)

- the Corangamite basin received the lowest streamflow compared to the average, receiving 20% of the long-term average volume

- the East Gippsland basin received the highest streamflows compared to the average: 1,249,108 ML, equivalent to 140% of the long-term average volume.

Table 2: Victorian streamflows

Melbourne system inflows

The annual natural inflows to Melbourne’s harvesting reservoirs can be compared to 2 different baselines: the long-term average (from 1913-14 to 2022-23) of 574,624 ML, and the average of the last 30 years, which is lower at 484,427 ML.

In 2023-24, inflows were 507,651 ML, 105% of the 30-year average. This is less than the volume of inflows received the previous year (880,729 ML, 182% of the 30-year average).

Inflows in 2023-24 were below the long-term average. This is the first time in the past 5 years, but the 21st time in the past 27 years, that inflows into storages have been below the long-term average.

Storages

Victoria’s major water storages can hold approximately 12,405 GL. Of this, Melbourne’s storage capacity is approximately 1,812 GL, and the capacity of the state’s major regional storages is approximately 10,594 GL. The combined volume of water stored in Victoria's reservoirs varies both within each year and between years.

Total Victorian storage levels started the year at 11,410 GL (92%) and peaked at 95% in October 2023 (compared to 98% in December 2022). Levels finished the year at 10,100 GL (82%) at the end of June 2024.

Total Victorian storages

Victorian major storages were 82% at end June 2024 (compared to 92% end of June 2023).

Melbourne storages

Melbourne storages were 87% at end June 2024 (compared to 92% end of June 2023).

Regional storages

Regional storages were 81% at end June 2024 (compared to 93% end of June 2023).

Regional storage levels

In 2023-24, total regional storage levels:

- started the year at 93% in July 2023

- peaked at 94% in October 2023 (compared to 99% in December 2022)

- finished the year at 81% at end of June 2024.

Melbourne storage levels

In 2023-24, total Melbourne storage levels:

- started the year at 1,672 GL (92%) in July 2023

- reached a peak of 1,756 GL (97%) in February 2024 (compared to 98% in November 2022)

- finished the year at 1,568 GL (87%) at the end of June 2024.

Storages in major urban centres

The total volume of water stored in Victoria’s major reservoirs has historically been at its highest following winter and spring inflows. Storage levels at the end of October are traditionally a good indication of water availability for the remainder of that water year.

Figure 6 presents end-of-October storage levels as a percentage of storage capacity for Melbourne and selected major regional centres from October 2003 to October 2023.

At the end of October 2023, storages were between 77% and 98%:

- The regional storages were all between 77% and 98%, lower than the previous year when regional storages were all between 94% and 97%.

- Melbourne’s combined storage level was 96%, similar to the previous year when it was 98%.

Response to availability

The volume of water available for consumptive and environmental uses will vary from year to year. This section details the management approaches applied in response to availability. The entitlement and planning frameworks include mechanisms to conserve and share water between users in response to seasonal variability and water shortages. The Victorian Desalination Project is a climate independent water source that enables the state to supplement the naturally occurring water supplies when needed.

We have provided more information on these mechanisms in How is water managed?

With slightly less water available in 2023-24 compared to the previous year, there were more restrictions on licensed diversions from unregulated stream sections, but seasonal allocations were similar. As in 2022-23, all towns remained on permanent water-saving rules (with no additional restrictions) and there were no temporary qualifications of rights to water.

There were 2 instances of water carting were required to address isolated water shortages in 2023-24 (see Statewide water supply).

More unregulated stream restrictions

There were more unregulated stream sections on bans or restrictions than in the previous year.

Similar seasonal determinations

Water share holders had access to about the same amount of water in 2023-24 as in the previous year.

Urban restrictions were the same

All towns remained on permanent water-saving rules for the whole of 2023-24, the same as the previous year.

Seasonal allocations

In 2023-24, seasonal allocations to high-reliability entitlements in all declared water systems reached 100%, the same as the previous year. In addition, all northern and southern systems received significant allocations to low-reliability entitlements, with 100% reached for all systems except for Goulburn and Loddon (77%).

By February 2024, all northern and southern systems had received seasonal allocations of 100% high-reliability water shares. By the end of the year, only the Wimmera Mallee Pipeline product, and low-reliability entitlements in the Goulburn and Murray did not reach 100% allocation.

Table 3: Seasonal water allocations in regulated water systems

Unregulated stream diversion restrictions

There were more unregulated stream sections with restrictions on licensed diversions in 2023-24 (Figure 7).

- The number of unregulated stream sections under restrictions and bans reached a peak of 80 in March 2024 compared to 52 in March 2023.

- There were 60 stream sections on restrictions at the end of 2023-24 compared to 43 at the end of 2022-23.

Desalinated water

Water produced by the Victorian Desalination Project is transferred into Cardinia Reservoir and combined with water sourced from upstream catchments and reservoirs, including O’Shannassy Reservoir, Upper Yarra Reservoir and Thomson Reservoir. The Victorian Desalination Plant can deliver up to 150 GL of water a year when operating at capacity.

No desalinated water was produced (0 GL) for 2023-24, compared to 4.1 GL produced in 2022-23.

Water use

In Victoria, water can be taken from reservoirs, streams and aquifers under entitlements issued and authorised under the Water Act 1989.

In addition to formally issued entitlements, the Act enables individuals to take water for domestic and stock use without a licence (for example, from a small catchment dam).

The volume of water taken presented in this overview and in the river basin local reports is reported as the volume of water diverted from a water source. It is the bulk volume of water extracted from the waterways, less any volume returned. Therefore, it includes volumes lost (e.g. to evaporation or seepage) from storages, channels or water supply systems after it is taken from the source.

We explain more about the water entitlement and planning frameworks in How is water managed?

Use by type

Table 4 shows the use of water in each basin. In some cases, these volumes differ slightly from the volumes of water taken under entitlements in each basin in Table 6. This is because Table 6 reports water taken under entitlements based on the source basin for each entitlement, while Table 4 reports water that was used within each basin. Some entitlements may source their water from one basin and then transfer it to be used in another basin. For example, in 2023-24, 1,305 ML was transferred from the Goulburn basin to supply urban use in the Yarra basin. In Table 6, the 1,305 ML is reported in the Goulburn basin as water taken under the entitlement, but in Table 4 the same volume is reported against the Yarra basin as water used.

In 2023-24, 3,919,830 ML of surface water was taken for consumptive and non-consumptive purposes (similar to the 3,462,528 ML in 2022-23).

Of this, 2,986,799 ML was taken for consumptive uses, about the same as the 2,850,249 ML taken in 2022-23. This includes water used for:

- irrigation: 2,155,499 ML (55% of total use)

- urban: 698,731 ML (18% of total use)

- small catchment dams: 89,632 ML (2% of total use)

- power generation: 42,937 ML (1% of total use).

In addition to the consumptive use, 933,031 ML was delivered for the environment under entitlements (24% of total use). This includes both in-stream and off-stream deliveries. There was an additional 18,366 ML of managed passing flows delivered in 2023-24. This was more than the 620,618 ML delivered in the previous year (612,279 ML under entitlements and 8,339 ML through managed passing flow deliveries).

Table 4: Surface water use by type

Entitlements and compliance

Entitlement volumes

Entitlements provide the basis for how water is shared. The total volume of entitlements changes slightly each year as new entitlements are issued or existing entitlements are modified.

All basins in the state have a cap, which limits the volume of water that can be allocated. In catchments that have reached the cap and allocated all available water within the limit, no new entitlements are created unless water savings are made, and so there is no net increase in entitlement volume. This cap and trade system means that the only way for a water user to get more entitlement is to purchase it from someone selling unwanted or unused entitlement.

Most basins in Victoria have reached their cap, and so only a minor change in the total statewide volume of entitlements on issue is likely to occur annually.

Here is the list of Bulk and Environmental Entitlement holders as at 30 June Visit the Water Register for up-to-date information on bulk entitlements.

In 2023-24, there was a net decrease in total entitlement volume of around 128 GL from 2022-23 (Table 5 and Figure 10). Most of this volume (124 GL) reflects a decrease in small catchment dam entitlement volume, which is represented by the estimated volume of use from small catchment dams for the water year. This approach is taken because not all small catchment dams are required to be licensed or registered under the Water Act 1989. The remaining net 4 GL decrease reflects smaller allowed entitlement volume changes in individual basins.

Changes to bulk and environmental entitlements

Several amendments were made to bulk and environmental entitlements in 2023-24, a summary of the changes is as follows.

Amendments as part of water recovery projects in Northern Victoria

Further changes to entitlements occurred in 2023-24 as part of the Goulburn-Murray Water Water Efficiency Project and Lower Murray Water Sunraysia Water Efficiency Project. These investments modernised water delivery infrastructure in the Goulburn-Murray Irrigation District (GMID) and irrigation districts in Sunraysia. Following completion of on-ground works and an audit process, the consequent water-savings were allocated as entitlements. These changes during the 2023-24 year include:

- changes to reflect issuing of 10,387 ML of water shares to the environment for water savings in the Goulburn and Murray basins

- changes to reduce the corresponding loss allowances underwriting water recovery in the Murray and Goulburn basins.

In addition, 4,016 ML of new Mitigation Water environmental entitlements was issued to the Victorian Environmental Water Holder (VEWH) from water recovered from the Goulburn-Murray Water Connections Project. These entitlements replaced the Environmental Entitlement (Goulburn System - NVIRP Stage 1) 2012 and the Environmental Entitlement (River Murray - NVIRP Stage 1) 2012, which were repealed on 20 June 2024.

Other amendments

Other changes to bulk and environmental entitlements include:

- changes made to reflect the issue of 5,588 ML of water shares in the Thomson basin to Southern Rural Water for water savings achieved through the MID2030 phase 1A modernisation project

- transfer of 3,330 ML from Yarra Valley Water to Gippsland Water and resulting new Gippsland Water Greater Yarra System – Thomson River Pool bulk entitlement

- minor amendments to the Greater Yarra System – Thomson River Pool bulk entitlements to reflect the transfer of bulk entitlement from Yarra Valley Water to Gippsland Water and the new Gippsland Water Greater Yarra System

- amendment to Melbourne Water’s 4 Melbourne Headworks System bulk entitlements to reflect the transfer and new Gippsland Water bulk entitlement

- changes to Tarago and Bunyip Rivers Environmental Entitlement 2009 to enable VEWH to store its share of inflows in unused airspace in Tarago Reservoir, when its own capacity share (3,000 ML) is full

- further changes to formalise and reflect the new Melbourne Water Storage Manager appointment across the Goulburn System Greater Western Water, South East Water and Yarra Valley Water bulk entitlements

- issue of 4,016 ML of new Mitigation Water environmental entitlements to the VEWH from water recovered from the Goulburn-Murray Water Connections Project. These entitlements replaced the Environmental Entitlement (Goulburn System - NVIRP Stage 1) 2012 and the Environmental Entitlement (River Murray - NVIRP Stage 1) 2012 which were repealed on 20 June 2024

All changes to bulk entitlements are administered under Part 4, division 1 of the Act and require consultation and consideration of matters including the impact on current users and the environment.

Table 5: Entitlement volumes by owner type

Water available under entitlements

Table 6 represents the total volume of water that was available, and taken, under entitlements in each basin in 2023-24. The volumes of water taken for each basin may differ from Table 4, where the volumes represent the use of water in each basin. Some entitlements may source their water from one basin and then transfer it to be used in another basin. For example, in 2023-24, 565 ML was transferred from the Kiewa basin to supply Beechworth in the Ovens basin. In Table 6, the 565 ML is reported in the Kiewa basin as water taken under the entitlement, but in Table 4, the same volume is reported against the Ovens basin where the water was used.

The total available water volume in Table 6 is the sum of: opening carryover, allocation issued and the net trade of water (trade in less trade out), less water lost to spill. Rules for carryover, allocation and trade vary between entitlements and systems, and not all concepts are relevant for each basin.

Table 6 shows that in 2023-24:

- there was 7,160,908 ML of water available under entitlements (more than the 6,610,602 ML available in 2022-23)

- there was 3,864,056 ML of water taken under entitlements (more than the 3,340,785 ML taken in 2022-23).

Table 6: Water available and taken under entitlements

Compliance

Compliance against water entitlements is reported in these Accounts in 3 areas:

- entitlement issued: that the volume of entitlements issued in a basin does not exceed formal caps or has not increased without appropriate approvals

- water taken: that the volume of water taken during the year does not exceed the volume considered to be available for consumptive and/or in-stream use during that year

- bulk entitlement provisions: that holders of bulk entitlements do not breach any provisions that are documented in their bulk entitlement orders.

Total entitlement volume

There was no net increase in the total entitlement volume from the previous year.

Total volume diverted

At a state scale, the total volume diverted under entitlements (3,864,056 ML) was within the volume available for the year (7,161,007 ML).

Individual bulk entitlements

No individual bulk entitlement holder took more than the annual volume made available to them.

Exceptions to compliance

Individual bulk entitlement holders reported 10 instances of failures and difficulties experienced in complying with entitlement provisions. More detail has been provided in the Barwon, Campaspe, Goulburn, Maribyrnong, Murray, Ovens, and Werribee basins.

Water leaving the basin

Water leaving the basin is water that flows out of basins at their downstream ends. This includes all water flowing through the system, excluding diversions and losses. In terms of water for the environment, it includes managed environmental water delivered in-stream, obligations on consumptive entitlements (such as passing flows) and above cap water. This water flowing through the system provides environmental, social, recreational and cultural benefits.

Although water leaving the basin provides environmental benefits, the proportion of flows leaving Victorian river basins is not in itself a reliable indicator of river health. This is due to the complex interaction of ecological processes and the seasonal variability of streamflows.

In 2023-24, at a statewide scale, water leaving river basins was lower than the previous year. A total of 19,028,210 ML left river basins compared to 41,530,538 ML in 2022-23.

As a percentage of statewide total flows in basins, water leaving the basin was similar to the previous year, with 90% reaching basin outlets in 2023-24, compared to 85% the previous year.

Table 7: Water leaving the basin

Trade

Water markets provide water users flexibility in the quantity and timing of their water use. For some parties water markets are key to their operations and they rely on allocation trade rather than entitlement ownership.

More allocation trade

The volume of priced trades in northern Victoria (1,444,995 ML) was the highest on record.

More net interstate trade

There was 100,961 ML of net water trade out of Victoria compared to 36,533 ML into Victoria in the previous year (excluding environmental water).

Less water share transfer

67,589 ML of high-reliability water shares transferred ownership compared to 89,101 ML in the previous year.

Note: Groundwater trade is covered in Statewide groundwater.

For further information:

- An introduction to the water trading framework in Victoria can be found in How is water managed?

- Additional information on Victorian water trade can be found on the Water Register .

- Trade of water in Victoria is subject to trade rules and limits. Information on trade rules can be found on the Water Register

Allocation trade

Water allocations can be traded subject to trade

Allocation trade has been broken down into 3 categories:

- Commercial trade indicates water transferred between water accounts at an agreed price.

- Zero-priced trade indicates a movement of water to another account for zero dollars, excluding any trades involving environment water accounts. These trade applications may indicate a trade between accounts owned by the same person or related parties, or carryover parking return.

- Environmental trade indicates trade between environmental water accounts, or zero-priced trades between private and environment water accounts.

In 2023-24, a total of 4,177,490 ML allocation was traded in Victoria, more than the total of 3,631,716 ML traded in 2022-23.

The vast majority of allocation trade occurred in northern Victoria (4,167,368 ML), with a small volume traded in southern Victoria (10,122 ML) and no allocation traded in western Victoria. In 2023-24, the volume of priced trades in northern Victoria was the highest on record for the 2nd year in a row: 1,444,995 ML. This is consistent with the trend of increasing allocation trade since 2007-08.

Environmental water holders use trade to move water across Victoria and between their accounts. Environmental trade made up 41% of the total volume traded in 2023-24, a similar proportion to the previous year. This includes water that was transferred to South Australia for delivery in the South Australian Murray system.

Table 8: Summary of seasonal allocation trade

Trade in northern Victoria

A total of 2,722,373 ML of zero-priced trade (both non-environment and environmental trades) occurred in northern Victoria in 2023-24. A total of 1,444,995 ML of priced trade (commercial trades) occurred in northern Victoria in 2023-24 (Figure 12).

Trade between VIC, NSW and SA

Water trade between Victoria, New South Wales (NSW) and South Australia (SA) is permitted subject to trading rules. Interstate trade of water can occur due to allocation trade or tagged trade. Tagged trade is when water used in one trading zone is sourced from a different trading zone. Victoria has tended to be a net importer of water over most of the past decade, with exceptions in some years, including when conditions are unusually wet in Victoria or dry in NSW.

In net terms during 2023-24, excluding environmental trade (Figure 13):

- Victoria exported 14,093 ML of water to NSW, compared to 12,892 ML imported in the previous year

- Victoria exported 86,867 ML to SA, compared to 23,640 ML imported in the previous year

- there was 100,961 ML of interstate trade out of Victoria. This is a change from the net total of 36,533 ML into Victoria in the previous year.

Water share transfer

Trade of water shares represents a trade of ongoing annual water entitlements in declared systems. Most of the state’s regulated water systems have been declared.

From 2009-10 to 2011-12, large volumes of water shares were transferred to the Australian Government as part of buyback programs under the Basin Plan, resulting in much higher overall transfer volumes.

In 2023-24, water share transfer across Victoria included (Figure 14 and Table 9):

- 67,589 ML of high-reliability water shares transferring ownership; less than the previous year (89,101 ML).

- 33,898 ML of low-reliability water shares transferring ownership; less than the previous year (47,497 ML).

Table 9: Water share transfers

Most of this trade occurred in northern Victoria, with a small amount in southern Victoria. Western Victoria does not have declared systems, so it has no water shares.

Unregulated surface water trade

Outside declared water systems, take and use licences allow water to be taken from either unregulated surface water systems or from groundwater, and to be used subject to the conditions defined in the licence.

Unlike allocation and water share trading, surface water take and use licence trading occurs more evenly across the state, with several trades in the west of the state. Trades as part of land transfers were the most common trade type.

In 2023-24, surface water take and use licence trading resulted in:

- 958 ML of unregulated surface water permanently traded (not as part of a land transfer), slightly more than the 869 ML permanently traded in the previous year

- 4,394 ML of unregulated surface water temporarily traded, more than the 3,144 ML temporarily traded in the previous year

- 10,620 ML of unregulated surface water traded as part of a land transfer. This was similar to the 11,634 ML traded as part of a land transfer in the previous year.

Table 10: Trade of surface water take and use licences

Trade in surface water take and use licences was less than trade in groundwater take and use licences. For information on groundwater trade see the trade section in Statewide groundwater.